—Fred Cutler, Associate Professor of Political Science

Back Story

Fred Cutler, teaching statistics to political science students, used Google spreadsheets for a few years as a Student Response System. Using anonymized student numbers, with each student having one row, he asked students to populate a shared spreadsheet with empirical research questions, definitions of the concepts involved, relevant research hypotheses, definitions and measurement strategies for variables, and so on. You can see it at http://bit.ly/380RP .

He also used shared spreadsheets for students to input numerical information such as their grandmother’s feelings about Stephen Harper and then used the spreadsheet to demonstrate various statistics and statistical concepts.

The Switch to Learning Catalytics

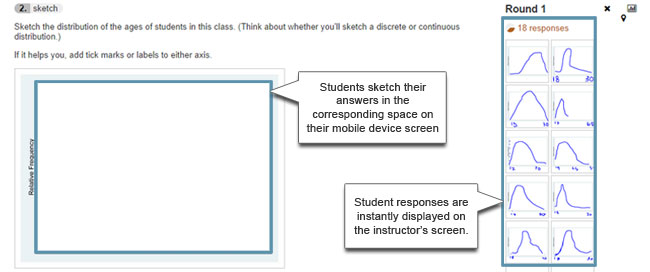

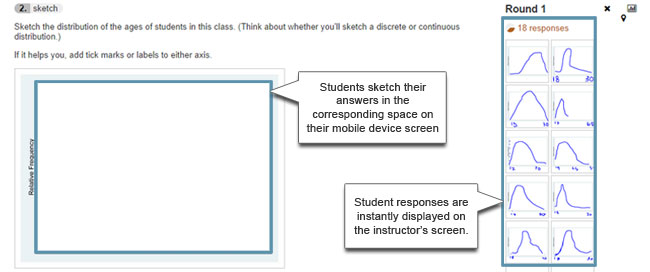

Fred recently adopted Learning Catalytics as a total replacement for powerpoint lectures. With Learning Catalytics he can ask students all kinds of questions, from multiple choice with one or many correct answers, to questions where students sketch or pinpoint an answer with their fingers on their smartphones. For students to literally get a feel for distributions, he asks them to sketch the age distribution of students at UBC and then the age distribution of the Canadian population. The results look like this:

Fred also uses LC for peer instruction, which reflects the genesis of the tool by Eric Mazur (Physics) and Gary King (Political Science) at Harvard . Using LC’s built-in technology, students place themselves in a seat map of the class and then respond to questions individually. After a question is answered, LC can group students based on their responses: it delivers a message to each student telling them with which other students nearby they should discuss the question. The questions may be traditional multiple choice, where students try to convince each other that their answer is correct, or the questions may be open-ended, such as the question Cutler asks his students (with no background reading or learning): “What causes attempts at military coups in developing countries”.

The learning objective around this question is not to learn what causes military coups, but rather to acknowledge the continuum from idiosyncratic causes to systematic, more predictable and generalizable causes. Student input ranges from “The dictator was hungover” to “the price of the country’s natural resources fell on the global market” and students get to see the huge range of responses. The instructor then uses that range of responses, pointing to some of them on the screen, to illustrate the methodological point he wants students to understand.